“When you are dead and in Heaven, in a thousand years that action of yours will make the Angels sing your praises.”

– Hannah Johnson, mother of a Northern Black soldier, writing to President Abraham Lincoln about the Emancipation Proclamation, July 31, 1863

Every few years, I take a trip to Washington, D.C. I enjoy reacquainting myself with the must-see monuments and others that have been added in recent years. But several years ago, I visited one which I had missed on previous visits: Lincoln’s Cottage.

Officially known as President Lincoln and Soldiers’ Home National Monument, Lincoln’s Cottage is a national monument on the grounds of the Soldiers’ Home, known today as the Armed Forces Retirement Home.

Given that Soldiers’ Home’s location in a leafy and calm section of the city, near what is called Brookland, I could understand why Lincoln and his family, seeking an escape from both the summer and political heat of downtown Washington, chose to reside there seasonally.

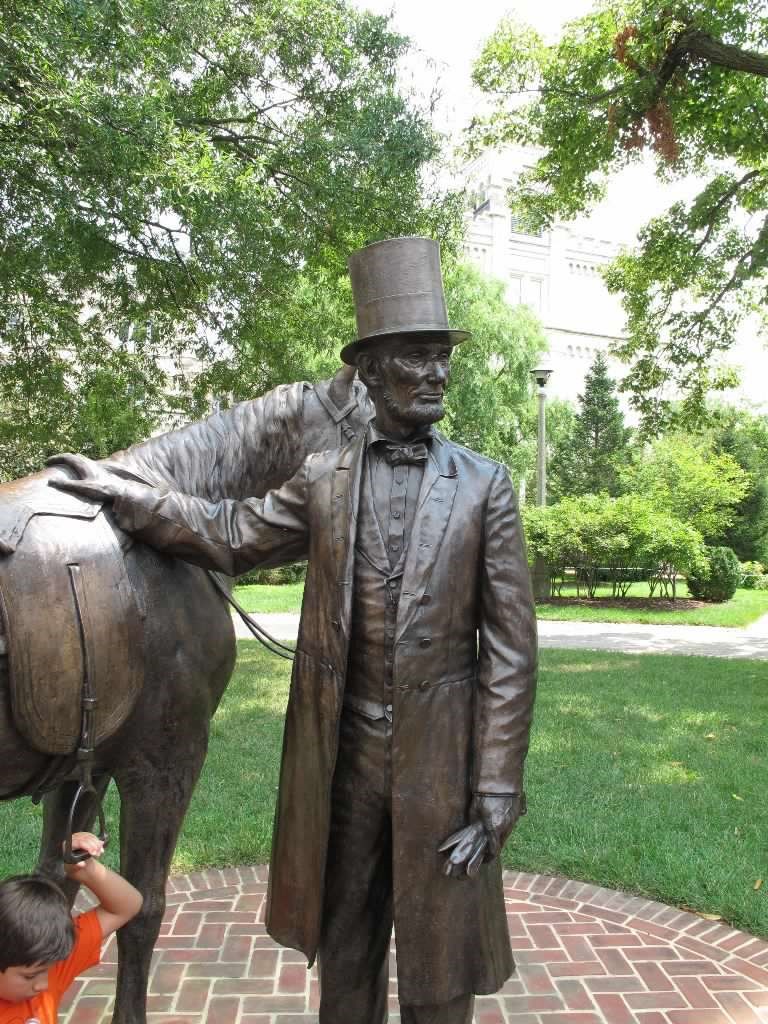

The tour I took of the charming, Gothic-revival style cottage and grounds informed that Lincoln lived there June to November 1862 through 1864. A life-sized bronze statue of Lincoln, his gaze turned towards the cottage, stands across from it. He wears his familiar top hat, which adds more inches to his already tall frame. His right hand rests on his horse, also in bronze, which, along with his owner, seems ready to move.

The tour I took of the charming, Gothic-revival style cottage and grounds informed that Lincoln lived there June to November 1862 through 1864. A life-sized bronze statue of Lincoln, his gaze turned towards the cottage, stands across from it. He wears his familiar top hat, which adds more inches to his already tall frame. His right hand rests on his horse, also in bronze, which, along with his owner, seems ready to move.

While a refuge for the Lincoln family, the cottage did not fully allow the President to escape his worries of a bloody civil war and from the issue of slavery. This became clear when my tour group entered the commodious library, in which was a long table covered with a dark green felt cloth. The guide then explained that this was the most important room in the cottage, for it was in that room and at that table where the President set down the preliminary draft of the Emancipation Proclamation. We all looked at the felt-covered table in respectful silence, each of us probably visualizing Lincoln’s tall and angular figure bent over the paper that would receive the first words of what became one of this country’s immortal documents. In another room, we saw a reproduction of the desk where Lincoln wrote the final version (the original is in the Lincoln Bedroom of the White House). But it was the green felt covered table that stayed in the memory.

Although only five pages long, written in Lincoln’s elegant script, the Proclamation was momentous when he issued on January 1, 1863, as the nation approached its third year, “that all persons held as slaves are, and henceforward shall be free.” Despite the embedded limitations of the edict (e.g. it would apply only to states that had seceded from the Union, leaving slavery untouched in the loyal border states, and the freedom it promised depended upon Union military victory), it had a seismic effect on the millions of enslaved people, many of whom had been in bondage since their birth.

Although only five pages long, written in Lincoln’s elegant script, the Proclamation was momentous when he issued on January 1, 1863, as the nation approached its third year, “that all persons held as slaves are, and henceforward shall be free.” Despite the embedded limitations of the edict (e.g. it would apply only to states that had seceded from the Union, leaving slavery untouched in the loyal border states, and the freedom it promised depended upon Union military victory), it had a seismic effect on the millions of enslaved people, many of whom had been in bondage since their birth.

Lincoln’s religious beliefs greatly informed his thinking about slavery and his decision to write the Proclamation. He was raised in an anti-slavery Baptist household but was deeply familiar with the King James Version of the Bible and quoted from it often. Though he never professed an orthodox Christian ethos, he frequently attended First Presbyterian Church with his wife. And while he was not an abolitionist, Lincoln found it increasingly strange and morally wrong that any man could dare to ask a just God’s assistance in “wringing their bread from other men’s faces.” After three long years of its bloodletting, Lincoln came to believe that the Civil War might be God’s exacting punishment for the sin of slavery. Slavery was not ordained by heaven, but an abomination unto it. As author Jon Meacham, in his recent book on Lincoln, And There Was Light: Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle, observes, “He moved toward emancipation amid a deepening sense that his duty lay in attempting to discern and to apply the will of the divine to human affairs.” (p. 15)

In the numerous portraits of Lincoln, we can discern the spiritual effects of Lincoln’s engagements with his difficult personal experiences (such as the deaths of his sons), as well as with the wrenching pain which the Civil War imposed on the country. Whether we look at those portraits on our rusting pennies, our worn five-dollar bills, or in the magnificent Daniel Chester French sculpture, the weight of Lincoln’s spiritual struggles is ever present.

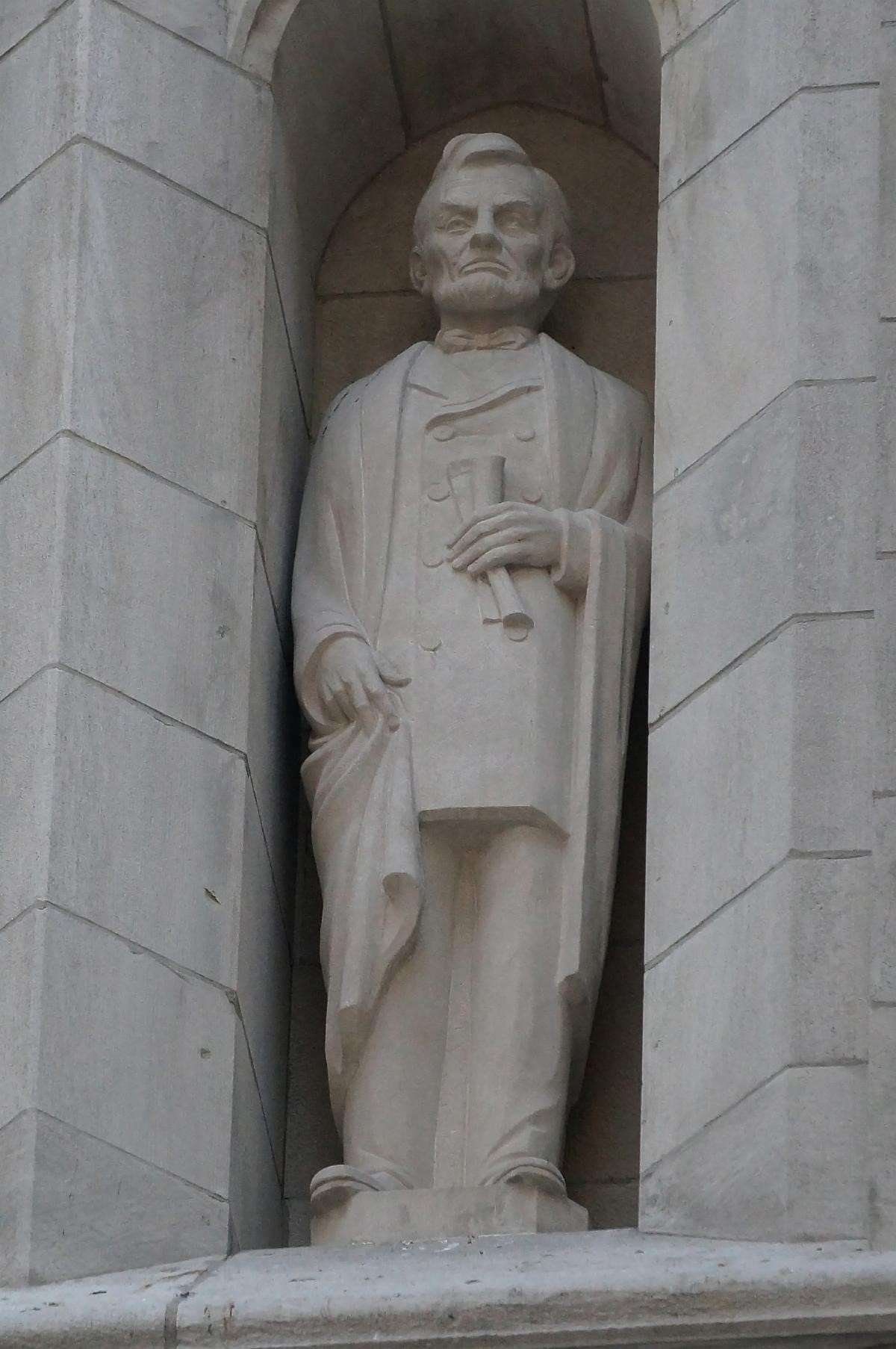

However, the Rochette and Parzini sculpture of Lincoln that has occupied its niche on our church since 1972 captures the unflagging resolve he presented to hold the Union together. But most striking is the rolled paper our Lincoln holds in his left hand and presses to his chest. It can be nothing other than the Emancipation Proclamation, which is his masterwork, as well as his secular saint attribute.

However, the Rochette and Parzini sculpture of Lincoln that has occupied its niche on our church since 1972 captures the unflagging resolve he presented to hold the Union together. But most striking is the rolled paper our Lincoln holds in his left hand and presses to his chest. It can be nothing other than the Emancipation Proclamation, which is his masterwork, as well as his secular saint attribute.

On the Great Reredos there is a statue of George Washington, the father of our country, who was also a slaveholder. On the church’s tower is Abraham Lincoln, a slave emancipator, whose immortal words fathered a new country.

This is the second in a series of four essays devoted to the Emancipators statuary, which is located on the tower of the church’s Fifth Avenue façade.

However, the Rochette and Parzini sculpture of Lincoln that has occupied its niche on our church since 1972 captures the unflagging resolve he presented to hold the Union together. But most striking is the rolled paper our Lincoln holds in his left hand and presses to his chest. It can be nothing other than the Emancipation Proclamation, which is his masterwork, as well as his secular saint attribute.

On the Great Reredos there is a statue of George Washington, the father of our country, who was also a slaveholder. On the church’s tower is Abraham Lincoln, a slave emancipator, whose immortal words fathered a new country.

This is the second in a series of four essays devoted to the Emancipators statuary, which is located on the tower of the church’s Fifth Avenue façade.

“I, Too”

by Langston Hughes (1901–1967)

I, too, sing America.

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Tomorrow,

I’ll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody’ll dare

Say to me,

“Eat in the kitchen,”

Then.

Besides,

They’ll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed—

I, too, am America.